I have been distracted from publishing for the past few months because I have been helping a friend who is slowly losing her sons.

My friend is a nice middle-aged American woman from New York state who converted to Islam several decades ago when she married her Afghan husband. Though she and her husband are hardly Islamist, they decided it would be best for their two sons to attend a Muslim school – in part because the public schools in their community are terrible.

After searching unsuccessfully for a Muslim day school, they happened upon a boarding school option in Buffalo: Darul-Uloom. They sent off their two boys hoping the experience would help them mature without the negative influence of drugs, gangs, and girls. But they started to realize – too late – that they had handed over their sons to be indoctrinated.

As the instructors at Darul-Uloom led her sons deeper and deeper into extremism, my friend watched devastated. As a convert, she lacks the self-confidence (and in her sons’ eyes, the credibility) to counter the messages they are getting at school. And she doesn’t know what to do. She turned to me for help, but I am struggling to give her advice.

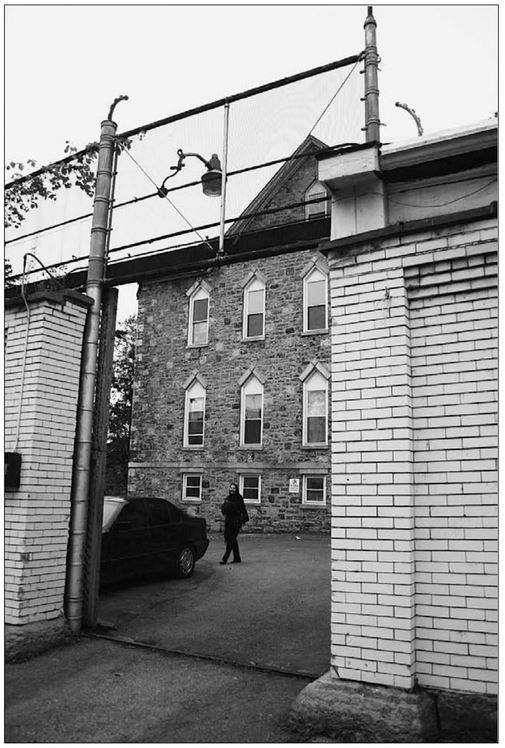

In the meantime, I’ve been reading up on Darul-Uloom – and came across this amazing report from inside the school by Professor Akbar Ahmed, in “Journey into America: The Challenge of Islam” – a 2011 book published by the Brookings Institution. Professor Ahmed reveals that the school is (appropriately) housed in an old Buffalo juvenile detention center. He describes his visit inside and then a subsequent dinner with Buffalo Muslims where the school’s influence is hotly debated.

Dear reader, you will not believe what’s going on right in upstate New York:

Run by tense, bearded, and silent men, the school is housed in a forbidding grey complex of buildings with dark and dank corridors that were once part of a juvenile detention center. A high wall topped by heavy wire netting protects the 6-acre compound and reinforces the image of a fort preparing for a siege…

We decided to turn up at the school unannounced. The two men in the administrative office were unhelpful and would not respond to our simple questions. We stood around awkwardly as they spoke with Faizan in Urdu. They did not even ask the women to sit as a matter of ordinary courtesy. I felt that these young men had lost their traditional South Asian manners and not quite acquired the American etiquette of greeting visitors with a smile and openness. They seemed suspended between two cultures.

Darul-Uloom and its separate sister school for girls had a total enrollment of some 350 pupils. The boys were dressed in an approximation of Islamic clothes: most wore skullcaps, others black turbans and long white shirts over baggy trousers; some wore American sweatshirts over these clothes to keep warm. They spent their time learning Arabic, Islamic law, and the Quran. We entered a class of about 100 students seated on carpets and memorizing the Quran in the traditional way by swaying vigorously. An amiable African American convert then allowed us to talk to his class of about twelve third-grade boys. The walls displayed several maps of the United States and the world, along with student drawings of the Kaabah in Mecca. Almost all the students said their life’s goal was to be a imam, mufti, or alim – the names for different types of religious scholars. When asked to define these words, one of the boys replied, ‘They give fatwas and are someone who knows everything.” Students said they wore this kind of dress outside of school and could not name a favorite cartoon or movie character.

Most of the boys were born in the United States, but their parents were from Pakistan, Egypt, Yemen, and other Muslim countries. When Zeenat asked those who had any non-Muslim friends to raise their hands, only one boy from Kenya put his up…

When I asked the office staff how these students coped with the “outside world,” one replied curtly, “We teach them deen [religion] only. As long as they keep deen, they will be okay on the outside. ” Improving relations between Muslims and other Americans, they said, “is really not our line of work. Our major concern is within this compound.” They were also evasive about American identity: “We don’t think about it.” When we asked for the schedule, it was given reluctantly and was in Arabic. All of the announcements were in Arabic and Urdu….

Faizan gave a dinner for us at his home on the last night of our visit, which allowed us to see the three Muslim models in the behavior and talk of his guests, numbering about thirty. Faizan himself is an example of the confluence of all three Muslim models. Educated in a madrassah in Pakistan, he defended the need for Darul-Uloom in the community; but he also believed in the modernist M. A. Jinnah, while quoting the Sufi verses of Rumi and Iqbal with relish. Ideological strains quickly surfaced that night.

Matters were complicated because of the different ethnic backgrounds of the guests, a mixture of South Asians, Turks, Arabs, and African Americans, including Imam Fajri Ansari, a leading local religious figure. At one point, the Turk became so exasperated that he accused the South Asians of being “racist…”

Farooq Maududi, a retired medical doctor, launched an attack on Darul-Uloom and its teachers. When Faizan suggested it was similar to Deoband in India, Maududi countered, “Deoband is enlightened, dedicated, and educated, whereas Darul-Uloom is a ‘criminal cult.” Privately, he claimed that the male instructors were preying on the young students in their charge. He called school founder Ismail a “rogue” who had spent time in a Saudi Arabian jail and was released early only because he was a hafiz, someone who has memorized the Quran.

This was no ordinary voice. Farooq Maududi is the son of Maulana Maududi, the founder of the Jamaat-i-Islami Party, which plays a significant role in South Asia, especially in Pakistan. The Jamaat-i-Islami is the South Asian equivalent of the Muslim Brotherhood in the Middle East, and the Maulana was a contemporary of Hassan al-Banna, founder of the Brotherhood. The Maulana died in his son’s care in Buffalo in 1979…

[Farooq] told me of his son who led a rock band, and I thought of how Maulana Maududi, who loathed the West, would have reacted to that news. Maududi’s presence that evening generated a buzz as he was considered something of a local celebrity-several guests whispered that he did not usually attend community events…

Many guests, including our host, argued that Darul-Uloom provided a real service to the community, offering “purity” and the training of popular imams who are now involved in interfaith activity. In response to the argument on behalf of purity, Imam Ansari suggested that Islam in America was more about “fighting oppression” than about purity. Some of the women were excitable supporters of Darul-Uloom and emphasized its “uniqueness,” explaining the institution needed to draw boundaries around itself, so did not require public relations.

As if this was not excitement enough, another drama was being played out in the next room. A prominent Pakistani physician who believed in modernist Islam pleaded with me to talk to his two sons who were being “dangerously influenced” by the literalist approach of the Darul-Uloom. The situation became complicated for me because the older son had approached me earlier, after my lecture at the University of Buffalo where Faizan taught. I could not fail to notice him. He had a big, bushy black beard and was wearing a white shalwar-kameez (traditional South Asian loose-fitting shirt and pants)…. Though willing to share his innermost reasons for supporting the Darul-Uloom, he did not want me to mention them to his father, or he would have a difficult time at home.

At Faizan’s dinner, however, the young man was a transformed person. He was defensive and nervous. Perhaps his father’s presence and guests had intimidated him. He begged to have his younger brother included in the conversation, and I went looking for him. Dressed in a smart Western suit with a neater and shorter beard than his sibling, the younger brother was in a corner rocking gently while he recited the Quran to himself. He seemed oblivious to his surroundings and not particularly concerned about joining the discussion, leaving his brother to talk on his behalf.

Just when I thought things could not get more interesting, the doctor’s wife joined in, speaking passionately for Darul-Uloom, while he stood by looking miserable. Then the wife of the older son, a white American convert to Islam who works at Darul-Uloom, spoke. There was no need to mix with other Americans, she said, but only with good human beings inspired by the Quran. When Zeenat suggested the Darul-Uloom might issue brochures describing the school’s work, she replied, “There is no need to worry about anything because everything is decided by Allah Subhanatallah.” She wore the hijab, calling it a “noble concept,” though her mother thought anyone wearing it was a “terrorist” and dressed for Halloween.

Darul-Uloom was a public relations disaster waiting to happen. I wondered what people like Steve Emerson, the terrorism czar of American media, would have to say if some controversy erupted around it…

Wow. There is so much to unpack here, my mind reels.

I think of the white American convert who sees no need to mix with non-Muslims. Her father-in-law the Pakistani doctor who sees his sons are being brainwashed but can’t stop it. The classroom of students where all but one have no non-Muslim friends. The imam who defines Islam in America as primarily about fighting oppression.

But the one shining ray of hope is Farooq Maududi. We South Asians know the havoc his father wreaked on our region and on our religion. It’s amazing to discover that his son has seen through all the crap his father spawned (like the Darul-Uloom school!) and that his grandson is in a rock band. Their example is an inversion of all the brainwashing going on elsewhere in the Buffalo Muslim community.

And Farooq Maududi nails it: the Islamists are a “criminal cult” – the sooner we all realize that, the better job we can do in trying to stop them, before they brainwash any more of our children.